By Jennifer Hlad

Crystal Bubulka always swore she would “never, ever home school.”

Then COVID-19 hit.

The social worker, Navy spouse and mother of three was working 60-hour weeks when schools in Hawaii shut down in March. Now she’s homeschooling her second-grader and pre-kindergartner while her oldest daughter attends virtual high school.

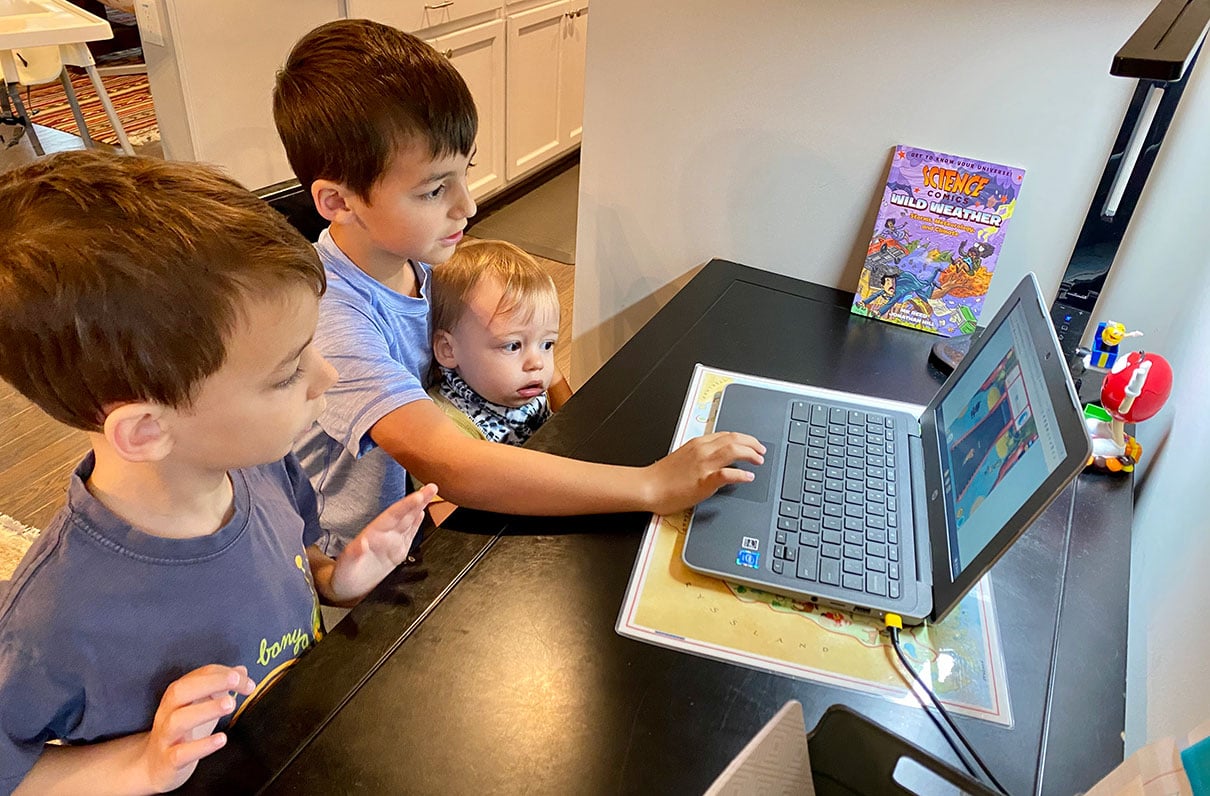

Cmdr. Christina Peterson, a Navy reservist whose active-duty husband is on sea duty, was on active-duty orders when schools shut down in Virginia Beach in March. Once those orders ended, she had planned to do “a ton of extra reserve work” throughout the summer and support exercises and events quarterly. Instead, she has been staying home with her three sons, the older two of whom are starting virtual kindergarten and third grade.

Bubulka and Peterson are just two of many military parents who have chosen to take time off work as they adjust to the challenges of educating their children during a pandemic. But not everyone has that choice.

Air Force Col. Rojan Robotham, a member of MOAA’s board of directors, works in a secure facility in the D.C. area — the kind of place where “you’ve got to show up every day, and you can’t bring your kids.”

But she can’t leave her 12-, 9- and 6-year-old sons at home alone, either. So her husband has been working from home, his career “put on hold, having to readjust, because there’s not child care,” she said.

Col. Rojan Robotham and her family. She and her husband are adapting to virtual schooling. (Photo provided)

Marine Lt. Col. Petra Lovetinska Seipel, serving in Okinawa, Japan, wasn’t sure what she would do when she learned the first few weeks of the new school year would be online only. Seipel is a group executive officer, and her husband — also an active-duty Marine — is attending a top-level school in the U.S.

When DODEA schools in Okinawa were shuttered earlier this year, Seipel’s husband was still living on the island, and they were able to find another military spouse who could pick up her 6- and 9-year-old sons from school age care and tutor them.

Unfortunately, that tutor moved away, and Seipel said she wasn’t sure she would have the time or the energy “to fulfill the education requirements for both of my children while trying to work full time and go to school myself.” She eventually pooled resources with another dual-military family, hiring a military spouse to supervise and assist all of the children while the parents are at work.

Lt. Col. Petra Lovetinska Seipel with her sons Max and Harley and her husband Lt. Col. P.J. Seipel. (Photo provided)

Robotham has tried to find a college student to help her children with school for a few hours each day, but has not been successful so far.

“There just aren’t a lot of options,” she said, and that lack of options is problematic not just for her, but for any mom or single father in the military.

For many military women, the decision to get out isn’t prompted by just one factor or event, Robotham said. Instead, it’s “death by 1,000 cuts … they finally hit that tipping point where you just can’t take it. And I’d hate for women to get out of the military or think that there’s no path of success in the military because of childcare.”

Even before COVID-19, finding “affordable, flexible child care” that is available early in the morning and later in the evening was “really difficult,” Peterson said. And when schools and day care centers first began shutting down, many commands expected parents to “figure it out for their kids, and then be at work,” she added.

Seipel said her boss has been understanding, but that even with “the most supportive command, at some point you will find that the credibility you built has eroded because you just don’t have as much time to devote to your job as your peers with non-working spouses.”

Bubulka, co-lead of the Hawaii chapter of Hiring Our Heroes Military Spouse Professional Network, said spouses with civilian jobs are also in a tough spot, because even if they can afford to quit, many are worried about a “COVID gap” on their resumes.

But military leaders can be creative in overcoming this challenge, Robotham said.

After Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida was damaged by a hurricane, base leaders had listening sessions and worked to create a plan for the “installation of the future.” Now, she said, the military has the opportunity to “reimagine childcare of the future.”

One potential solution, at least in the short term, is creating learning pods within squadrons or communities, she said.

“If we’re trying to be open and inclusive and have working mothers in the workplace, then we need to reimagine, we need to expand the bubble of what childcare looks like,” Robotham said. “We have to imagine the solution. … The great thing that could come out of COVID is that we’ve done something really awesome with child care.”

In the Air Force, they talk about barriers, she said. “This is a barrier, for women staying in the military, women being in the military, women having families in the military.”

“I want to serve. I enjoy it. But I also am a better officer when I’m not worried about my kids,” she said.

Jennifer Hlad is a freelance writer and editor and the spouse of a Marine Corps officer. She is former journalist for Stars and Stripes and has lived in Bahrain and Japan.

MOAA Knows Why You Serve

We understand the needs and concerns of military families – and we’re here to help you meet life’s challenges along the way. Join MOAA now and get the support you need.