When Albert Cliette volunteered to join a new unit seeking the Army’s most daring warfighters, he already had proven his leadership prowess and courage — by jumping from airplanes at airborne school.

But when he arrived at the newly formed Ranger School at Fort Benning, Ga., in 1950, he and other black soldiers were reminded they weren’t equal and were pulled away from white soldiers to train, eat, and sleep. It was a gesture of racism Cliette, 92, hadn’t experienced during his childhood in Detroit.

[RELATED: Leading the Fight: MOAA Recognizes Black History Month]

“I guess for the kids that were born in the South and had grown up in the South, to them, it was normal,” Cliette said, recalling his early years in the Army in the late 1940s. “But to those of us from the North, it was a cultural shock.”

Cliette and the other men quietly fought in Korea as the Army’s little-known, all-black 2nd Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne). When they returned home from combat, the unit deactivated as the Army integrated. But even with integration, black soldiers — especially in the South, weren’t always welcomed home as war heroes.

Today, nearly 75 years after Cliette accepted his first assignment, the Army has become more diverse than ever. This year, the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., announced it will graduate the most diverse class at any point in its 217-year history – including the highest number of African-American women, at 32 officer candidates.

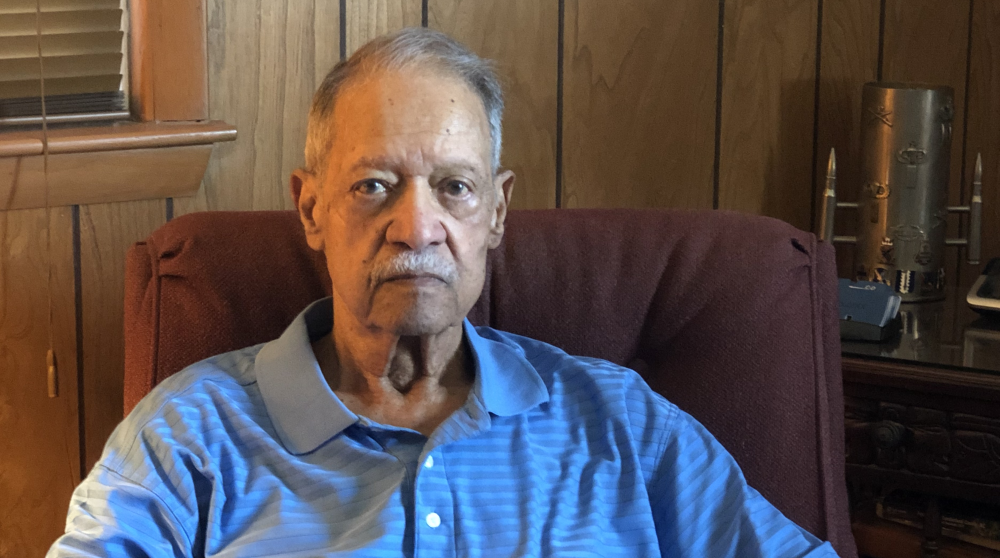

Albert Cliette retired in 1975 at the rank of sergeant major, after reverting back to enlisted in 1956. (Photo by Amanda Dolasinski/MOAA).

“I guess … I had hoped that we set an example of what they could do,” Cliette said. “I kind of hope (people) look at the way things were at that time and how much advancement has been made since then and come to terms with it. I would hope they would see that we made a difference. We can achieve the same things.”

Likely the last living officer of the Ranger company, Cliette, now 92, served an Army career that spanned 30 years from the end of World War II to the Vietnam War. He walked in as a company clerk and left with awards distinguishing his accomplishments with Special Forces during deployments to Korea and Vietnam. He retired in 1975 at the rank of sergeant major, after reverting back to enlisted in 1956.

For a black man from Detroit who never much paid attention to the odds against him, his career solidified a way forward for the young black men and women who came after him.

“I take some pride in being part of it, which helped toward integration,” Cliette said of his time in the all-black Ranger unit. “You know, proving that you can do it. The military leadership looked down on the black troops as primarily service troops. They treated you like that – a second-class citizen. A second, but unequal Army. I wasn’t raised that way. They wanted you to accept the status quo and you’d do everything in your power to change it.”

[RELATED AT SOC.MIL: 'When Men Don't Panic']

Cliette’s service started in August 1945, after he graduated from high school. He served as a clerk — or “usual gopher” — until May 1947 and left service to return home to Detroit.

Less than a year later, he re-entered service looking for adventure. He was assigned to the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment after he completed Airborne School and Officer Candidate School. He sought the chance to attend Ranger School when the Army announced plans to form an all-black unit.

A few years before the unit’s formation, President Harry Truman issued the executive order abolishing discrimination in the armed forces based on race, color, religion, or national origin. Despite the order, some units were slow to integrate.

Upon graduation, the 2nd Ranger Company immediately deployed to Korea.

About two months into combat, Cliette was shot twice — suffering a wound to his leg and miraculously surviving a shot through his helmet. Unconcerned for his safety, Cliette said the wounds simply “slowed him down.”

He would later receive the Silver Star for his valor during that battle on a non-descript hill.

“If the (enemy) had been at a different angle, it would have went right straight through the helmet, through my head,” Cliette said. “But it deflected enough. It just put a hole in the helmet and ricocheted around and came out the backside, I guess over my shoulder. I took the helmet off and looked at it and said a silent prayer: ‘Thank God he missed.’ ”

Cliette used a compression bandage to cover the wound in his leg. Once the gunfight waned, he was transported to a hospital in Germany, where he spent about two months recovering before he rejoined the Rangers.

As he was riding a train back to meet his unit, he overheard some troops talking about a combat jump into Munsan-ni to cut off retreating Communist forces. Cliette said jumping was a paratrooper’s dream and knew he had to be part of it.

That jump was eventually canceled, but a new airborne assault named Tomahawk was planned for a point further north.

Cliette made history by joining his comrades on what Army Special Operations historians have said was the first combat parachute jump ever made by Rangers.

The company parachuted into Munsan-ni with the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team and later attached to the 7th Infantry Division to defend Hill 581 during the Battle of the Soyang River. They experienced significant causalities but proved their mettle as they held onto territory with less than half the men most infantry companies required.

Before the men returned home from Korea in 1951, the Army fully integrated, thus deactivating the unit. Cliette returned to Fort Bragg, N.C., and pursued a career in the 82nd Airborne Division and later Special Forces.

He lived on post and stayed away from town, avoiding racism that lingered in the South. But on the battlefield, Cliette mixed in with white soldiers and found not just a mutual respect but also friendships.

“Once they started accepting me as equal on my job performance,” he said, recalling the turning point in his service. “Personally, I didn’t care if they liked me. As long as I did the doggone job that I was assigned to, followed the orders given, that’s what mattered. I wasn’t up there to make friends. I was up there to do a job. After you work a while, friendship would gradually emerge.”